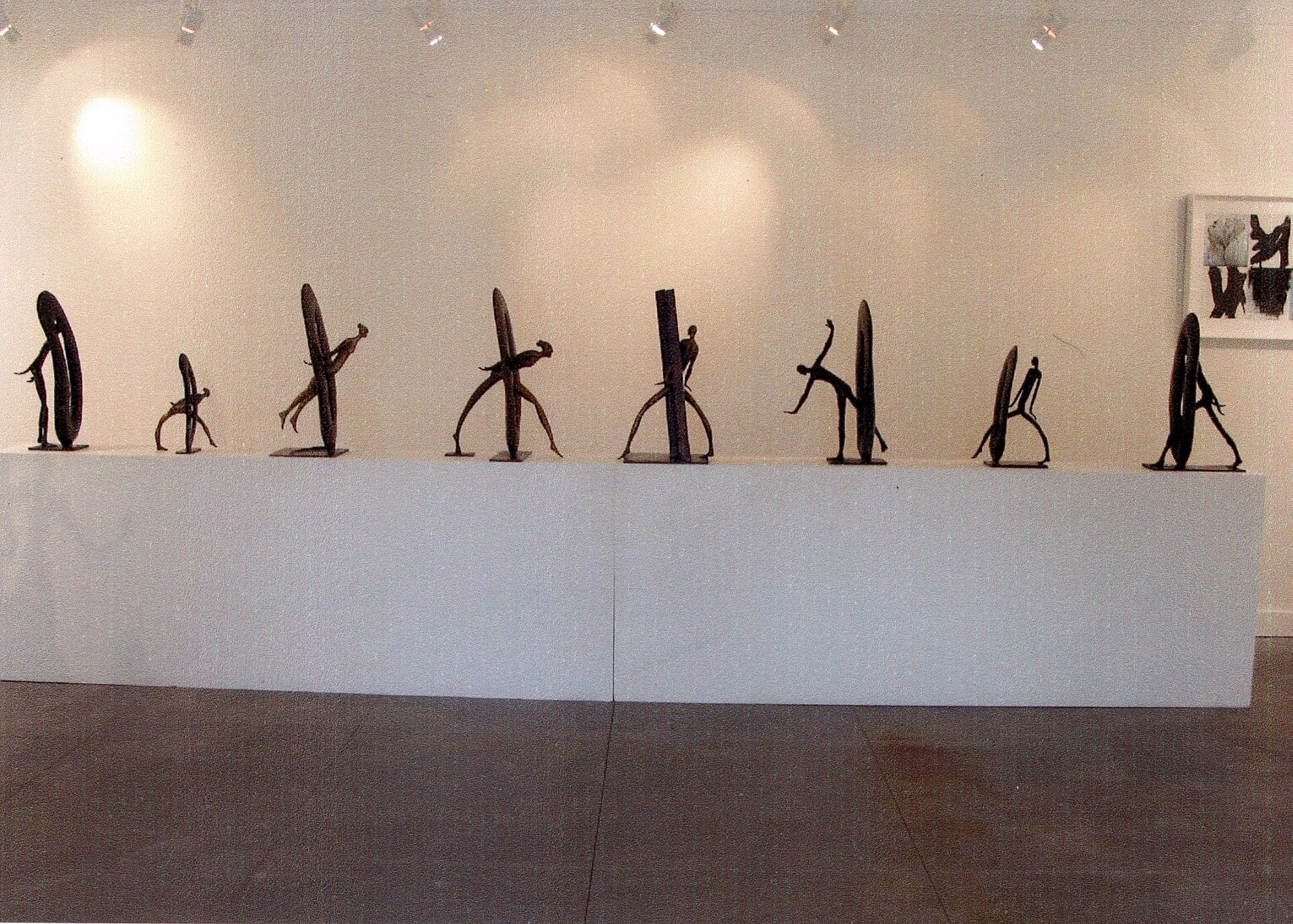

February 7 - March 2, 2008 Gods, Devils and Men

February 7 - March 2, 2008 Gods, Devils and MenSolo, Black Barn Gallery, Havelock North

Text

It is some part of basic instinct that produces figures of evil. A cultural mythology creates him in morality tales. The devil, whether as a trader for Faust’s soul, for youth with Wilde’s Dorian Grey, as God’s errant right-hand angel, or in all its ritualised forms in other cultures it becomes a solid figure with which to characterize moral choice, a vision for storybooks for adults and children alike. The invention of the devil is as old as time, inherited from tales of our ancestors as obediently as their genes.

But there is another side to the myth that slides easily from evil into mere naughtiness. When you devil an egg you add curry powder to the cooked yolk to give it a gastronomic kick. A devil’s food cake is chocolate, rich and dense, appealing and tantalizing, amounting to tangible desire, something so delicious you are unable to resist.

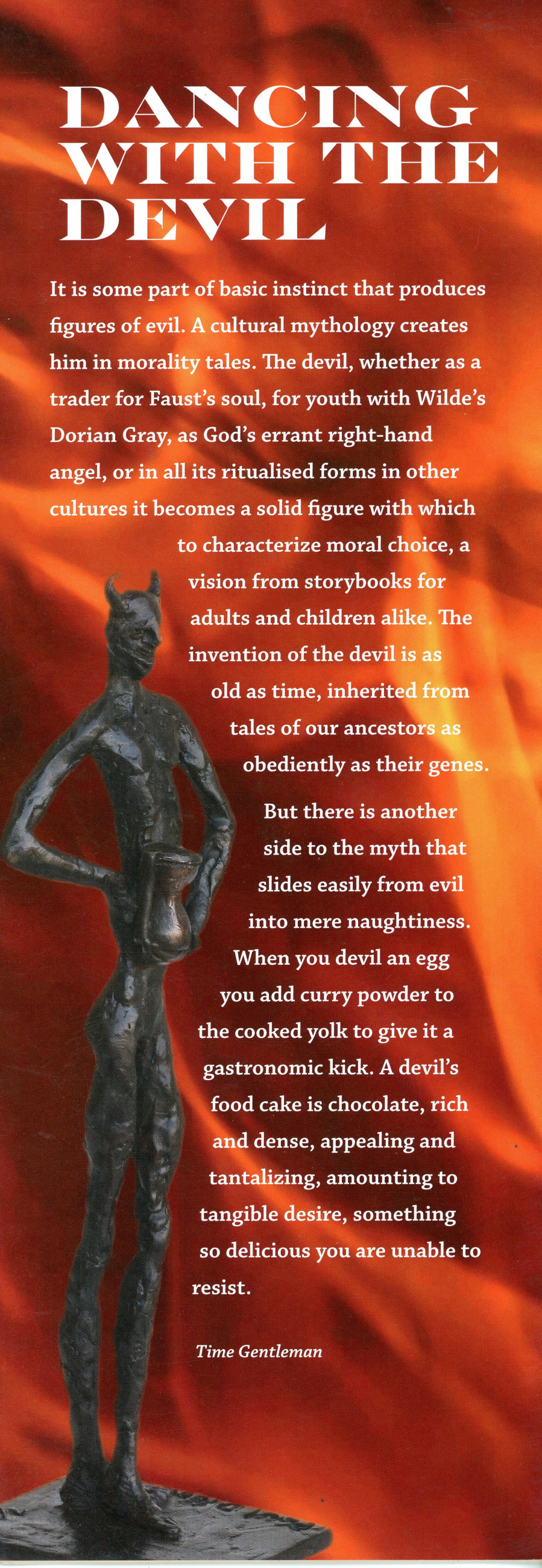

Paul Dibble, whose oeuvre contains a wealth of stories both specific to New Zealand and to the basic nature of all man’s humanity, has taken this character and made it into a series of smaller sculptures. They are a series of staged productions, like scenes from a soap opera, the devil as protagonist in each sequel. These are stories where the personified creature plays to, and plays up to us, the viewer. In the studies the devil, a natural actor, turns eloquently and parades, face turned towards us as if imploring the viewer to act as witness to the scene.

Dibble’s devil is really a rather grotesque and scrawny form. He is hard to believe as being the portrait of the personification of evil. More, he seems part jester, trying to humour us, a figure of devilish humour, with impish charm. He has sleek limbs as if of rubber. If you shook his hand it could melt, with languid fluidity, into a puddle in your palm. Yet he is strong, holding, with ease, a woman riding bare back. His face seeks us out as if recognising that we understand the plot and are somehow implicated. In him we see every used car salesman that sold us a dud, every politician that guaranteed a tax break, every lawyer that promised a quick settlement; the look slippery, wily and full of charm.

On the one hand these are whimsies; the artist’s hands look to have been playing, pulling out limbs, all bumps and bulges, expressive and with a freedom in rendering so they are relaxed and celebratory rather than carefully studied.

But there are more earnest topics in them. The devil may be a charming rogue and we feel drawn to him. Empathetic even, but he is meant to be standing in for evil. He is a real life taunt. As silly a mythical creature as he seems he is what must be reluctantly accepted in some form when, in a predominantly Christian country, we acknowledge existence of God. To have Good and belove in goodness entails existence of antithesis: Evil.

Such talk makes us uncomfortable these days. It is not the Victorian times when, with a firmly determined view of the world, people were classified as damned of saved. Now we exist in a world where there is tolerance, where each and every wrong is studied for its list of extenuating circumstances, where people are thought of as products that are formed from circumstance, sins perpetuated against them giving rise to “badness” in generation cycles that we hope to manage and alter. Political Correctness has tried to extinguish the devil and his realm.

It is in respect a return to the philosophical realm of ancient times. In polytheist religions their evil gods were not so much serious entities, but more imps and tricksters. Instead of good and evil their classification was a subtle but distinct variant of good versus disorder. Chaotic or disorderly removes all blame and guilt from proceedings, suggesting instead innocent malfunction. So renderings of Beelzebub, Satan or Lucifer, all these labels of evil that would be given seem out of step. But belief in the standard Christian God entails recognition of one of these beasts or what they presume to stand for. Dibble is taunting those to whom religion id held sacrosanct. With that classic New Zealand humour he is pulling our leg gently but also questioning in an act of defiance. Is this Evil, this rogue figure that flaunts himself before us? Was this the figure that witnessed the Big Bang, laughing that science tricked us into believing in a formulae for the world’s birth? The devil in one study stands quizzically looking at Darwin who is reduced to a crusty bust, long dead in his role as unknown foot soldier in the task to challenge God. Darwin is gone while our wily serpent lives on. These two correlations to science, descriptions of the beginning of man and the world in terms of physics and the biology of evolution, are a reference to the long controversy of science versus religion that has captivated debate for generations.

Another sculpture shows him seducing the photographer who earnestly tries to capture the impossible image. In ‘Dancing with the Devil’ he is moving with a rabbit, the Easter Bunny perhaps, as fictitious as he is; an absurdity of suggestion, two myths moving in tempo.

With all these dreams and fancies, these playful renderings of sacred mythologies of man, just remember the devil is in us all and with us always in waking and sleeping. So hop into bed, pull up the blankets so your shoulders don’t get cold, cuddle down, for it may be a long cold night in hell.