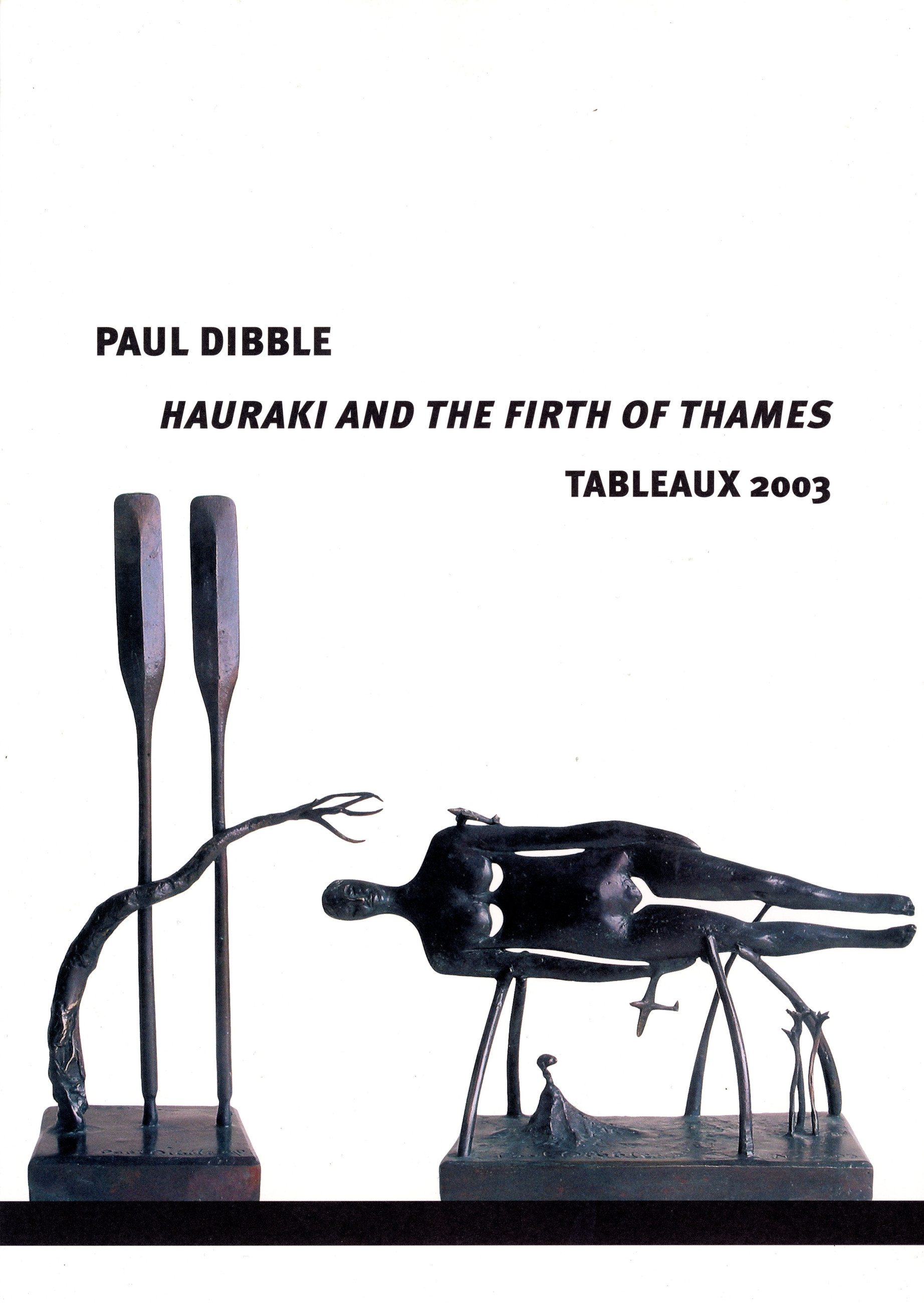

April 7 - April 26, 2003 Hauraki and the Firth of Thames

April 7 - April 26, 2003 Hauraki and the Firth of ThamesSolo, Bowen Galleries, Wellington

Text

A majestic female form magically levitates: fake props of spindly branches hold her impossibly above the landscape. The land below her shows her immense size. She is noble and timeless, floating eternal, making up part of the heavens.

A light bulb illuminates the undersea world, guiding fishermen to spear their catch.

Two oars stand supporting a knotted wind-weary Pohutukawa tree. The simple careless gesture gives at once a feeling of casual nonchalance and abandonment.

A bird lies beneath an umbrella. In this held instant of time, is it being offered protection as it would normally expect from a canopy of trees?

These works are placed alongside each other, standing one after another in line.

The tableaux should be read like a sentence that never ends. Each of the sculpture’s parts has its own narrative, yet each is also a part of the whole never-ending story. They link not as a comic strip, where we must read each in sequence, but as a cluster of dreams, of snapshots from an old photo album or bedtime stories from a child’s memories. Together they create a scene, not a story from beginning to end, but an understanding, created in bits of place and time.

This second tableaux is a grouping of stories that create one history.

Dibble’s first tableaux was created in 2002 and combined some 30 elements, stretching 7.3 metres. It spoke of the stories of his childhood home, Waitakaruru: where the owl sits on the water. This new tableaux, from the same location, speaks again of the small world of his boyhood in the Hauraki Plains, but has reached out in flamboyance and scope. The tales are more fanciful and wild. No longer are they just simple icons – some so small they could be held by a young boy’s hand. Now they are elaborated into complex narratives. The works encompass a wider New Zealand, not just his small piece of homeland, but more of the land and its history.

The dreamy qualities of the first tableaux have become a staged performance; the simple embroidered into complex and sophisticated fabrications. Instilled in the dream is now a theatrical resonance. Mad historical tales come to life and become a surreal, baroque opera.

Although constructed of static bronze, a moving narrative has been created, one that produces an emotional mix of lyrical fun, interwoven drama, quiet harmonies and romantic nostalgia. There is dialogue. Elements agree with and reject each other. They echo and interrelate. Some link and position themselves as allies. Some act out a production performed by several members of the cast, jumping from one work to another to complete the tale.

This tableaux is titled Hauraki. Its name, meaning the north wind, appears as its own signpost, a koru filigree within the tableaux. In our displaced land at the bottom of the Earth we seek north as the Europeans talk of going south for warmth. North has the lure not just of sun-filled holidays, but historically of food and survival. These works are a walk along the Hauraki coast and its history, happening upon boats and sea life, beached whales and lighthouses that beamed warnings.

The head of Captain Cook is pictured fittingly antipodean upside down. He grins manically, balancing on his chin a sprouting potato, his most successful if unglamourous gift. It enabled new sustenance for a Māori population. Cook’s botanist, Joseph Banks, his face represented like a trophy, is gathering specimens – he holds out a newly discovered kauri branch. Their travels along the Hauraki coast were well known; at one stage they travelled miles inland up the Waihou River, stopping to find a kauri tree to replace a broken mast.

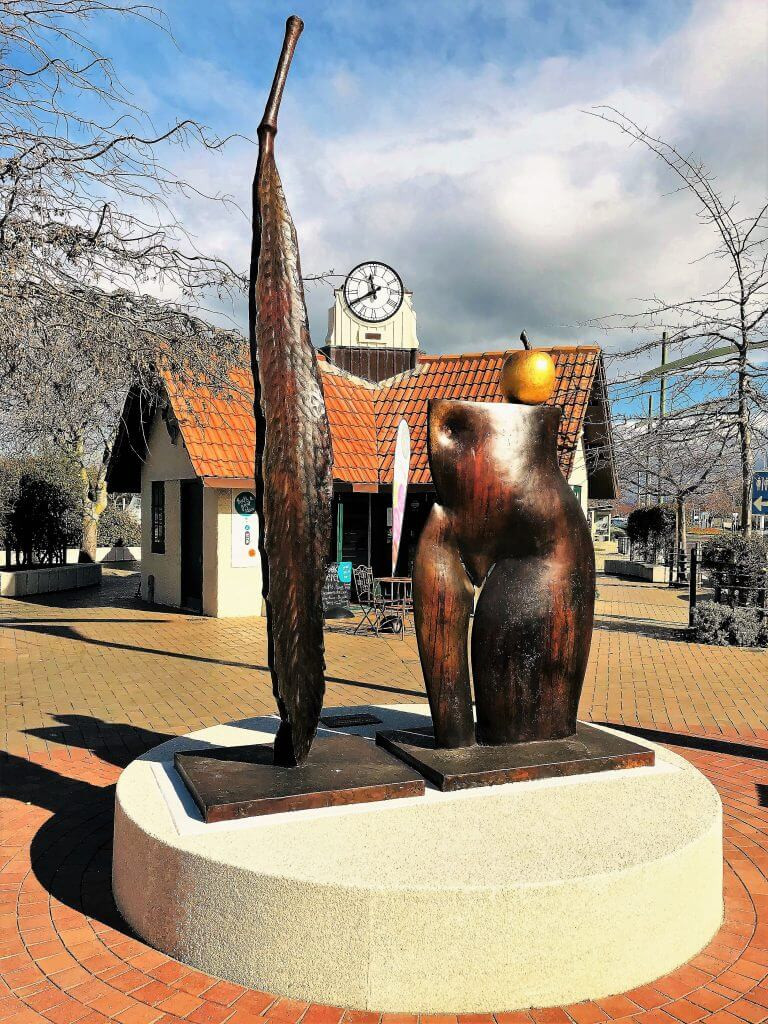

Other elements of the tableaux stand as relics, mounted on their square pedestals as treasured archaeological remains that could be from the cases of museums, or religious artifacts enshrined. And lurking, we see references to former times. The artist’s own sculptural past appears in new guise. The farmer stands again, once more naked and in gumboots. A fish dances on its tail with a Pacific lei. They also form a part of this epic.

The elements don’t just exist as narratives but are sequenced to play aesthetic games, intermingling as a masterful pick-n-mix of shape and mass; the straight and structured next to sensuous curves. The detail of fern frond is played off the simple structure of an urn. Thin, wavering forms stand next to the voluminous. Negative spaces are playfully repeated against positive forms. Patterned reproduction of shapes occurs throughout the series; the held kauri branch doubles the fern’s form. Oars, goal posts and straight cypress trees count out a rhythmic downbeat as vertical lines.

And so the sculptures whisper their fables, making up Paul Dibble’s anthem to a New Zealand childhood.

The fish-hook stands upright. Is it a historical reference to the tools of the early Māori, or does it refer to a pre-history, when Te Ika-a-Māui (the North Island of New Zealand) was pulled from the sea?

Cook and Banks: We can imagine their discussions as they walk along the coast, perhaps over the same paths that a young Paul Dibble would tread, Banks pointing out a botanical specimen as yet unknown in Europe, commanding his artist to construct a drawing, maybe collecting a fern to press in a book. Cook might comment on the oncoming clouds and the weather, straightening his hat and hurrying them back to the boat.

A stingray floats by, its edges rippling, curling up to reveal a delicate underside. It floats across the waters of the Hauraki Gulf.