November 18 - December 5, 1998 Paul Dibble

November 18 - December 5, 1998 Paul DibbleSolo, Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland

Text

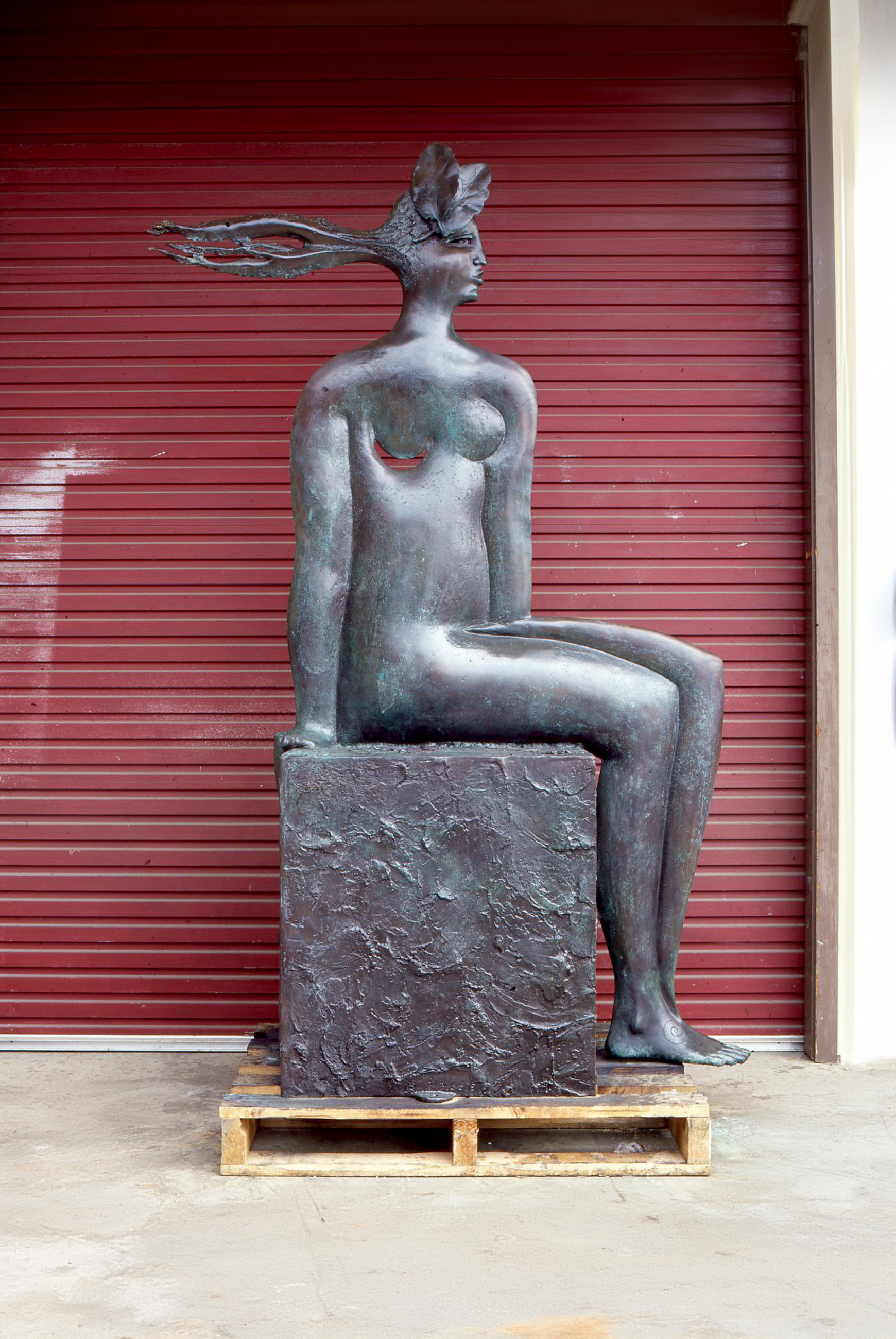

In the brief history of Pākehā sculpture, cast bronze has never flowered as it has through the last decade in the work of Paul Dibble. Bronze has had its New Zealand moments before, of course, most notably in the competing athletes and marching protesters Greer Twiss made in the late ‘60s, but the intrinsic nature of the material and the vision of the artist has seldom been so in tune as they are in the work of this sculptor.

Few sculptors have worked in bronze on this scale either, or with the freshness that informs Paul Dibble’s work and again, apart from Twiss, few in any medium have been so confident with narrative as Dibble – or so playful with it.

It is significant that Dibble casts his own work, a freedom that is reflected in both the scale of the pieces and the innovations obvious in their forms. It is clear that the sculptor has often arrived at formal solutions in anticipation of foundry problems, so what may have seemed a compromise has, in his work, become a strength. The flatness of profile he exploits in many of these works for example.

Bronze is a demanding material and it has a vocabulary of its own. In cultures as diverse as Etruria and the Kingdom of Benin, in artists as different in their times and points of view as Degas or Cellini, the medium asserts itself. There is a fluidity about it. It seems to insist on narrative. Whatever the vast gulf of time between them, an Etruscan Hercules, a Giacometti figure, an Indian temple toy, the rabbit on a Persian helmet seem, if not of a family, at least as twigs on the same family tree. To that tree Dibble has added icons as idiosyncratic as gumbooted farmers tossing their dogs, race horses and cups of tea.

There are, of course, a whole lot of simple explanations for this apparent consistency in the medium. Mostly the images cast in bronze come from the sculptor’s hand modelled in wax. In sixteenth century Benin or twentieth century Palmerston North, there are a lot of natural similarities in what the modelling hand will produce, the marks it will leave and the plastic forms that will evolve inevitably from the process. Perhaps that directness accounts also, for both the narrative and the playfulness of bronze.

Then too, there is consistency about the chronology of cast bronze. It is not a medium that has popped up at random times and random places. It is a sophisticated technology, not a naturally evolving process, like carving for example. For the most part, it has been a technology transmitted from culture to culture.

There are direct links between the cultures of Etruria, Greece and Rome, between Europe and China, China and India, between the Renaissance rediscovery of classical art and nineteenth century France, between Portugal and the Kingdom of Benin. (Paul Dibble hasn’t gone around with his eyes shut either.) Obviously quite a bit of iconography got transmitted with the process and while the main features of each particular culture will be distinct, a vocabulary of images and a peripheral playfulness seems somehow consistent to the medium.

One of the great delights of Paul Dibble’s work is that it asserts the European traditions that form the second stream in New Zealand’s bicultural mix. It is a slight shock, but nonetheless a pleasant one, to be reminded that the modernist traditions of the European twentieth century are also available to us.

The forms of Archipenko or Lipchitz, for example, are part of our experience. It is a point made as strongly by Dibble’s most recent work as it was earlier by Dick Frizzell’s Tikis. The icons of European modernism are there to be adapted and translated just as readily as those of the Pacific. In one of these works, for example, what might have been the strings of a lyre in an Archipenko have subtly transmuted into a sheet of corrugated iron in the Dibble.

One other aspect of Dibble’s work, impossible to avoid, is its great good humour. There is about his work, a rugged wit. Tears may be shed for the lost huia, as in A Tribute to Friends I Never Knew, but we are seduced into sorrow, rather than confronted by it. There is a very Antipodean dimension to Dibble’s mythology. These might be historic figures, but it is a very accessible kind of heroism.