July 12 - August 7, 2004 Soft Geometrics

July 12 - August 7, 2004 Soft GeometricsSolo, Bowen Galleries, Wellington

Text

Paul Dibble’s New Zealand workshop sits in a landscape of broad plains and big skies, which are echoed by the wide spaces and high ceilings that allow it to fulfil its multiple functions. It could be argued that the building is his most remarkable work; and one that continues to grow, like a magical machine divinely engineered to turn his concepts into a physical reality.

Some sculptors we have come to know are sophisticated specialists, modelling in clay and wax, dispatching their work to the foundry for strangers to complete. This studio is different, for the foundry lies at its heart. Here, the sculptor determines and directs the entire artistic process from the first sketch to the final polishing, working alongside his assistants, teaching as he goes.

The constant presence of the artist ensures the finest measure of control. The subtlest of adjustments can be made at every stage, moving this element a millimeter or two, re-sanding a surface, softening the texture on a wax model, reapplying a patina of colour. And sometimes, too, there are great courageous acts, when whole components are removed and recast.

The works we see emerge from this workshop, this complex and focused space. Here are created these soft organic shapes with their cool clean lines, from sweat and labour, fire and heat and endurance, paper and clay and metal – and from thoughts, stories, people and ideas, inspiration, vision.

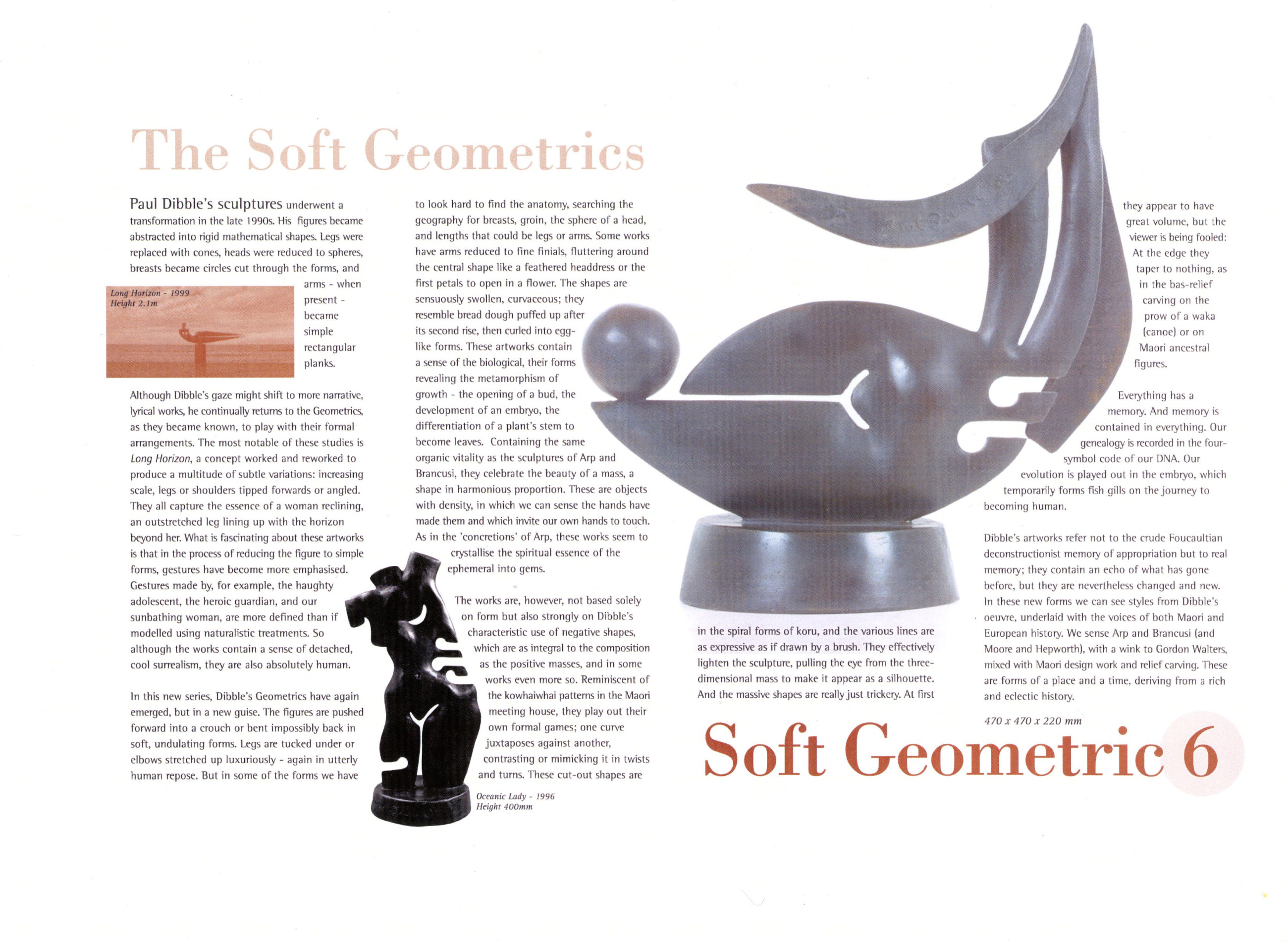

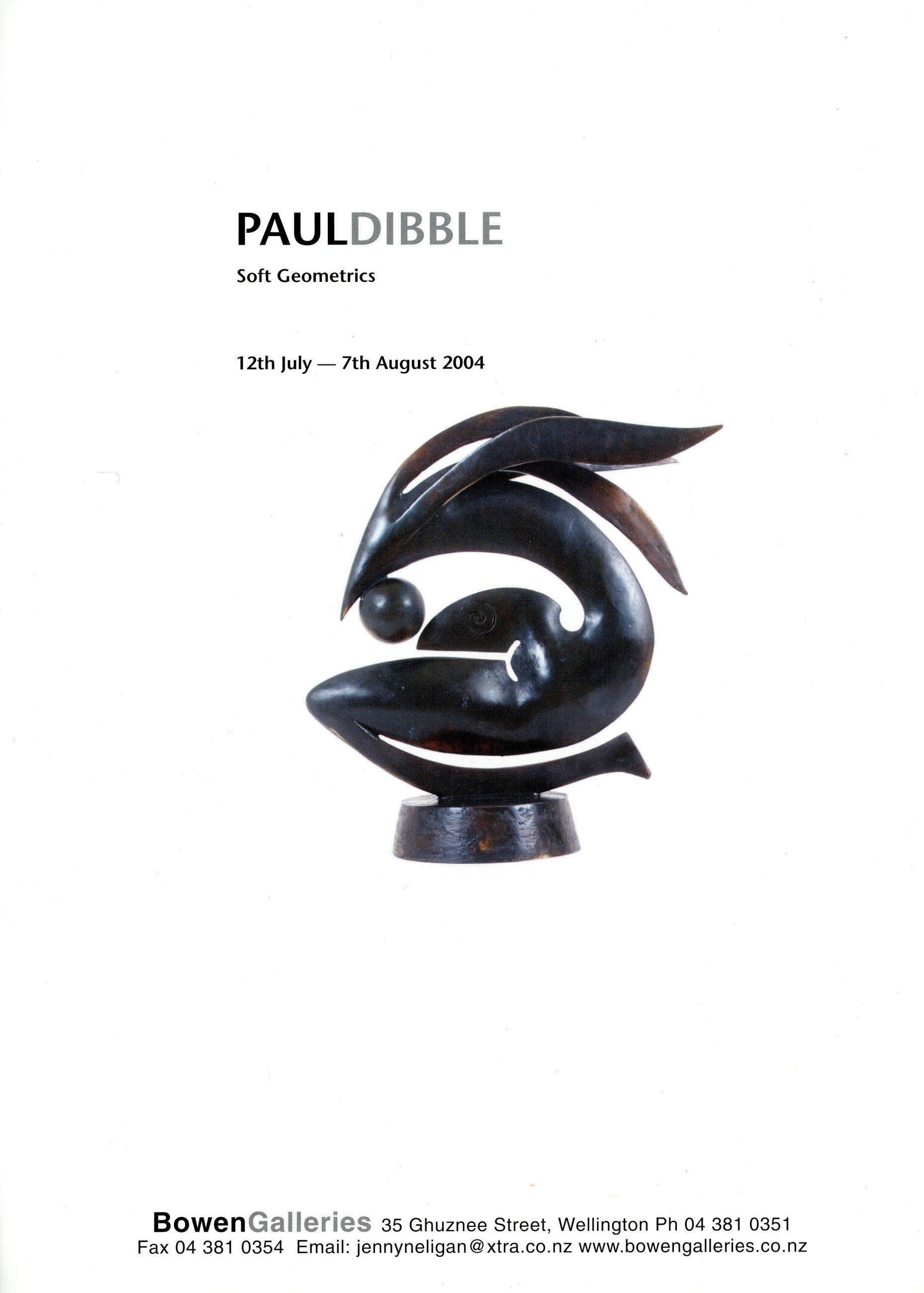

Paul’s recent works exist in what will eventually be seen as a distinct period with its own time frame. Their name, Soft Geometrics, encapsulates both their soft swell and curve and their link with an earlier series of geometrics that used harder mathematical structures of cone and sphere. Based loosely on the female form, these works are pulled and puffed into sensuous volumes, some with tiny limbs finning out from the main form, reminiscent of insect wings, the arms of dancers or flower petals. They have an organic vitality, an echo of European modernism in the South Pacific.

Here, the round has been chiselled to wafers, facades of masses, disappearing into thin lines when seen side-on, like the prows of waka. Incised patterns, some bearing the kowhaiwhai motifs of the Māori meeting house, cut through the solid forms, amplified in silhouette by their darkly contrasting colour. The importance of negative space in both Māori art and in the works of such modernists as Henry Moore is shrewdly observed by Dibble, and he manipulates negative space as fluidly as the form itself.