June 25 - July 7, 1990 Sculpture by Paul Dibble

June 25 - July 7, 1990 Sculpture by Paul DibbleSolo, Bowen Galleries, Wellington

Text

The period 1990 to 1993, in Paul’s vast history of art, when his sculpture career finally was getting going, hitting his straps, he concerned himself with what was, essentially, storytelling.

Growing up on a farm in Waitakaruru, an isolated area in these times, a visit to Thames was considered a big day out. When Dibble left to go to Art School and the big city lights of Auckland, he relished the change from this rural life which he then perceived as dull and monotonous. But by 1990, in the provincial city of Palmerston North with his own young children, he looked back on early memories with lenses misty with emotion.

The stories told in his youth, of heroes and overcoming obstacles, he returned to, bringing these to sculpture with a viewpoint that was profoundly different and his own. The stories are of a loosely woven narrative, the more wonderful for their spill into exuberance and humour.

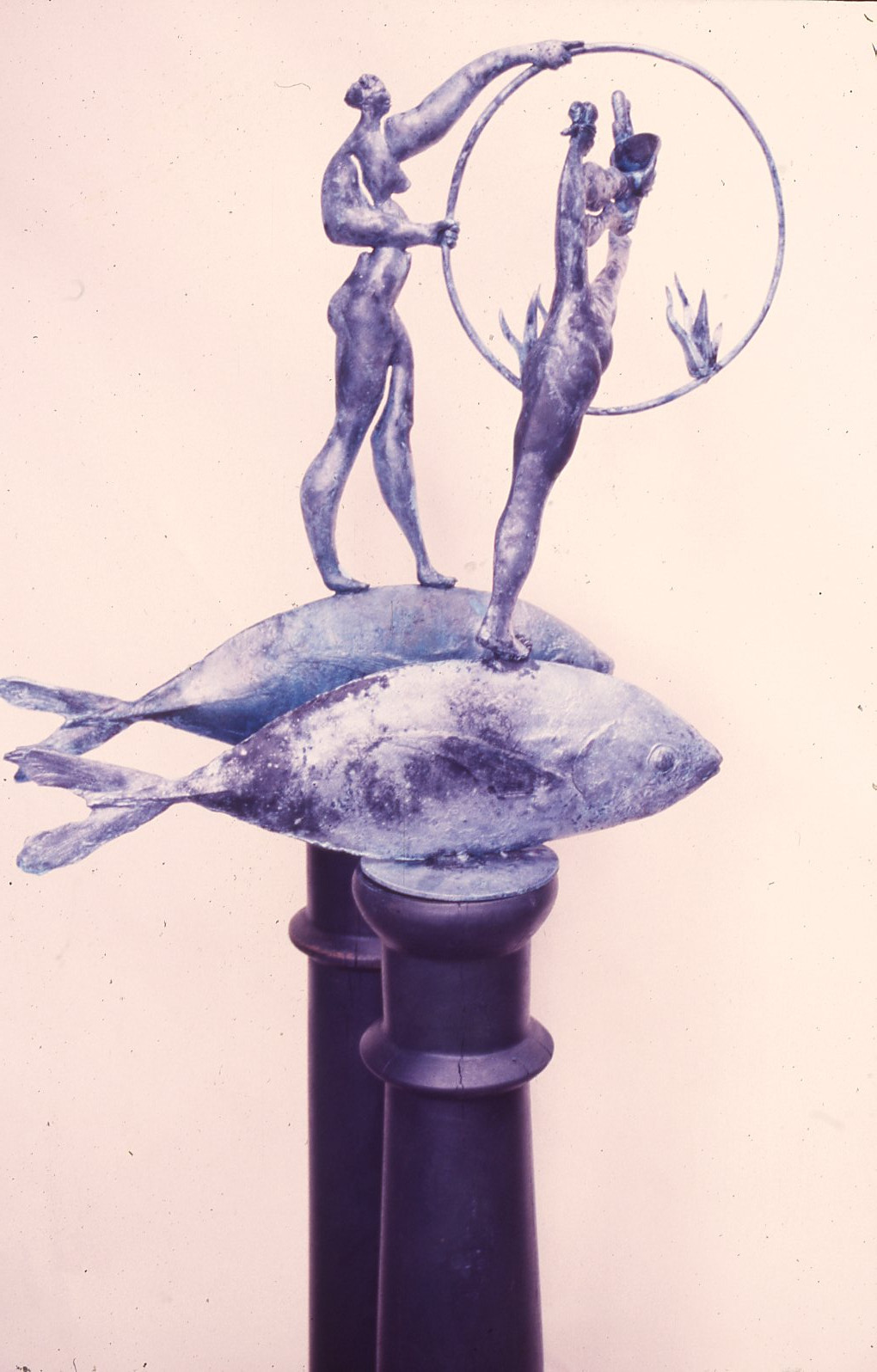

Although it is only a three-year period, as each of these years clocked over, the storytelling works underwent a change not just in the themes they visited (a crude division is the line-up of 1990 acrobats, 1991 mermaids and 1992 farmers), but also in the way the forms were worked – the delicacy of the modelling and in technical expertise.

The first work of the period, which slips just before this artificial framework, but which was part of the 1990 exhibition at Bowen Galleries, is Pacific Balance, 1989, part of the Manawatu Art Gallery Collection and still a pivotal piece in the artist’s work history. The female stylised figure, so different to any European statuary with its thin edges and partially abstracted form, is our New Zealand Boadicea. She is the hero of this tale, part circus performer, carefully standing on a plank which in turn is on a ball on a stand, a precarious tower that could easily tip (ass about face as Dibble might say). Props on three sides pull the work into the three-dimensional and help hold her in position. These sprout leaves making the props more delicate and more contradictory. Are these branches come to life? Or have they been cut from the foliage for a ramshackle event? The arm on her hip emphasizes the showmanship of the trick and her chin is held high while the fingers on the other hand are splayed (as if to say “ta da”), acknowledging the skill of her performance.

Another prop holds what the balancing act is for, a piece of sea. We recognise it, as a whale’s tail appears that has plunged into a meaningless ocean and a boat sails. An exotic parrot is perched on the edge. In his irreverent fashion, it is a fable about how precious Paul’s island home is. In a quote from the period, he noted “… a Pacific that is brutalised and loved … always finely balanced and always vulnerable.”

This sort of mythology weaved its way into other works. Several borrowed the Celtic icon of the Greenman, seen by Dibble on his travels, decorating European cathedrals (often as gargoyles spitting water collected from roof tops). These leafy heads Dibble applied to his figures, the crown of leaves also suggesting Pacific headdresses, so becoming a cross-over of European ideas transplanted in a new Pacific land.

One of these notably was scaled up large; Pacific Throne 1, 1990 which become Pacific Monarch, 1992 outside of Te Manawa. A Greenman who held a Huia on one arm appeared in the work Tribute to Friends I Never Knew, 1991 then further developed in 1998. This was the first Huia to land in Dibble’s artwork, something that would later develop into a grand theme.

But accompanying these more serious custodians were the circus acrobats proper. In Monument to Ben, 1992 the figure is jumping through a flaming hoop with a bucket of water, expressing the idiotic behaviour of human beings. In Looking for a Place to Settle, 1990 a strange man is walking on his hands while on his legs he carries a host of building materials he can use to build a home, the plump bob (marking “an intention to settle” as the artist would say) dangling behind him and even a chicken in a crate part of the hording.

There are other casual heroes – saving whales, rescuing fish, the Tuna doing a double act on an upheld plate. There is an ease about these works, a comic quality of humanness, even in many of the sideshow titles like The Dancing Fish Act, 1990 or The Wall of Death Act, 1990. They were children’s stories for adults, and even children’s stories for children, the influence of his own young evident, Daniel’s small constructions making their way into pieces of the works. These are fables where there are heroes protecting and saving, jesters perhaps but with courage in their perilous acts.

One of the features of the works of this period, and stretching out beyond, is the use of columns and stands. Getting artworks off the ground was an issue for the artist. This was an important intent, to make works that would stand tall and upright. But there was the punishing cost of trying to cast large stands, his own prices still at that of an emerging artist. So instead, he designed wooden bases, turned by woodworkers, New Zealand mock versions of European columns, often painted or with a lintel structure connecting them for a shelf. The idea was expanded to use old telephone poles, these with rounded bottom and top supports disguising their origins, achieving a more rugged quality. These unusual stands, some accompanied by fabricated supports were present right through the period and beyond. They complimented the technique also seen on many of the sculptures at play, a using of bits and bobs, assemblages of items in a method calling back to earlier works.

Overall, the balancing feats, playful characters and the use of props give the works a humour and vital quality. It belies the heavy seriousness of the materials they are made from and separate them from the visual heaviness of European traditions. For Dibble this sculpture was from a land separate, a new land of props and temporary structures, of fake building facades and signage, that was very different.