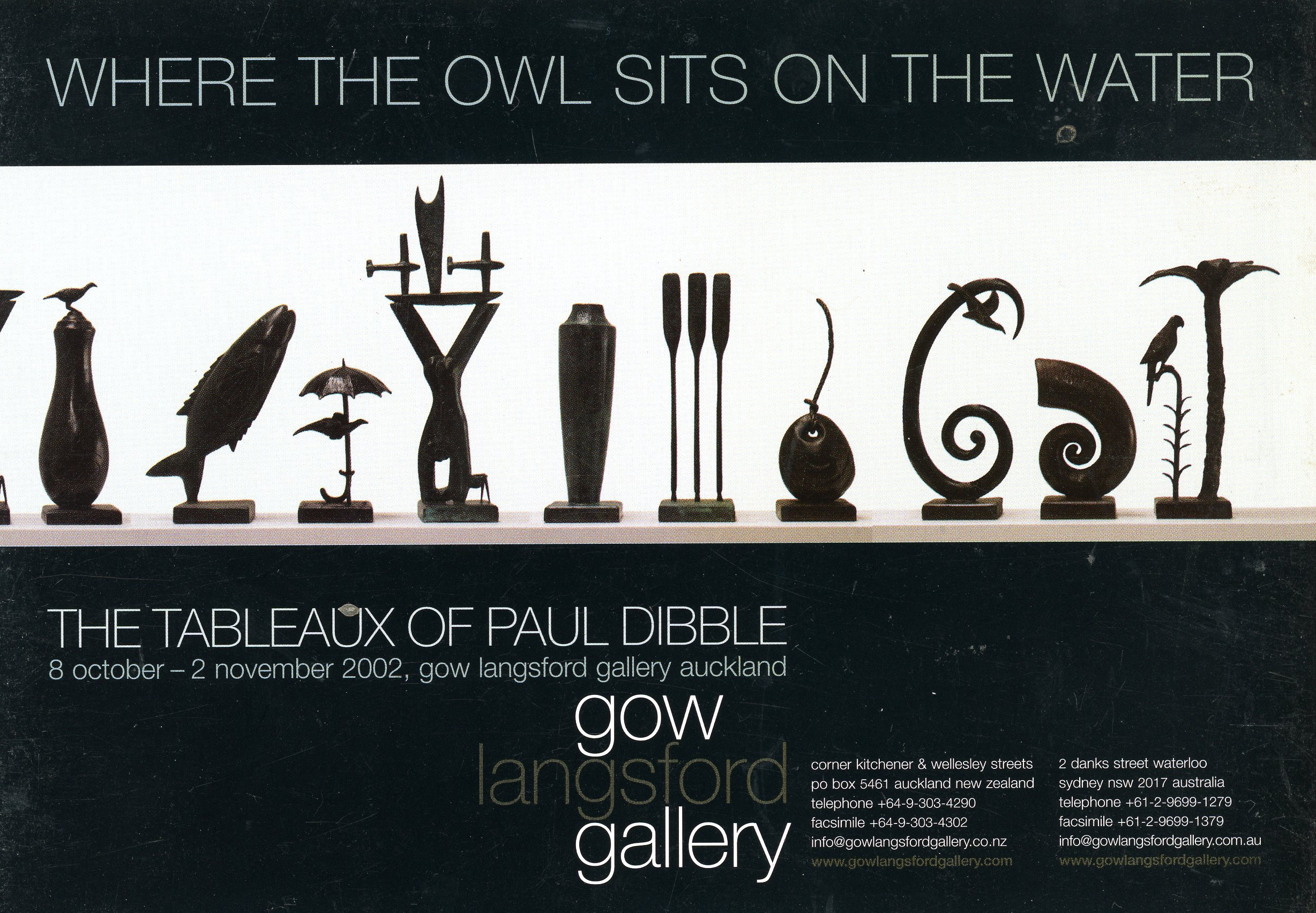

October 8 - November 2, 2002 Where the Owl Sits on the Water, The Tableaux of Paul Dibble

October 8 - November 2, 2002 Where the Owl Sits on the Water, The Tableaux of Paul DibbleSolo, Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland

Text

When sleep falls, in that semi-vacant phase, the mind quietly meanders through old familiar memories, to a gentle calm place - a space with sweet harmonies, fresh air and blanketed warmth. In this voyage before sleep, the mind can move with subtle grace through lingering images of the past. These images are the tableaux, falling one after another - elements of one man’s memory stretching out into a line. Some of the images we see with absolute clarity, some become symbols or have only parts rendered, some have been mixed with a fantasy world and some are from dreams.

And so we might imagine Dibble slumbering, and before us here are the products of those dreams. They gather as a timeline – a long, stretched series. But also, when arranged in groups of two, three and four, they play out their own parodies and create visual narratives. These are the autobiographical imaginings and memories of dreamtime, a story land mixed from quick snapshots of Dibble’s boyhood.

Dibble’s glances back to his origins have happened in various stages in his sculptural career. The best known were those artworks produced in the ‘80s and early ‘90s when we saw the jubilance of a series known as the Hinterland, which stood as a tribute to rural New Zealand. Many of the works featured what looked to be madcap circus antics. Farmers stood in one gumboot while balancing farm dogs; mermaids brought sheep to safety over waters. They were lyrical and their mood was of the impulsive and frivolous.

In this second retracing, the atmosphere is instead a quiet, dreamy rendering, a rendering broken into short glimpses and images followed one after another in the same way a story might unfold - a collection of bit-sized pieces that together summarise a history and a land.

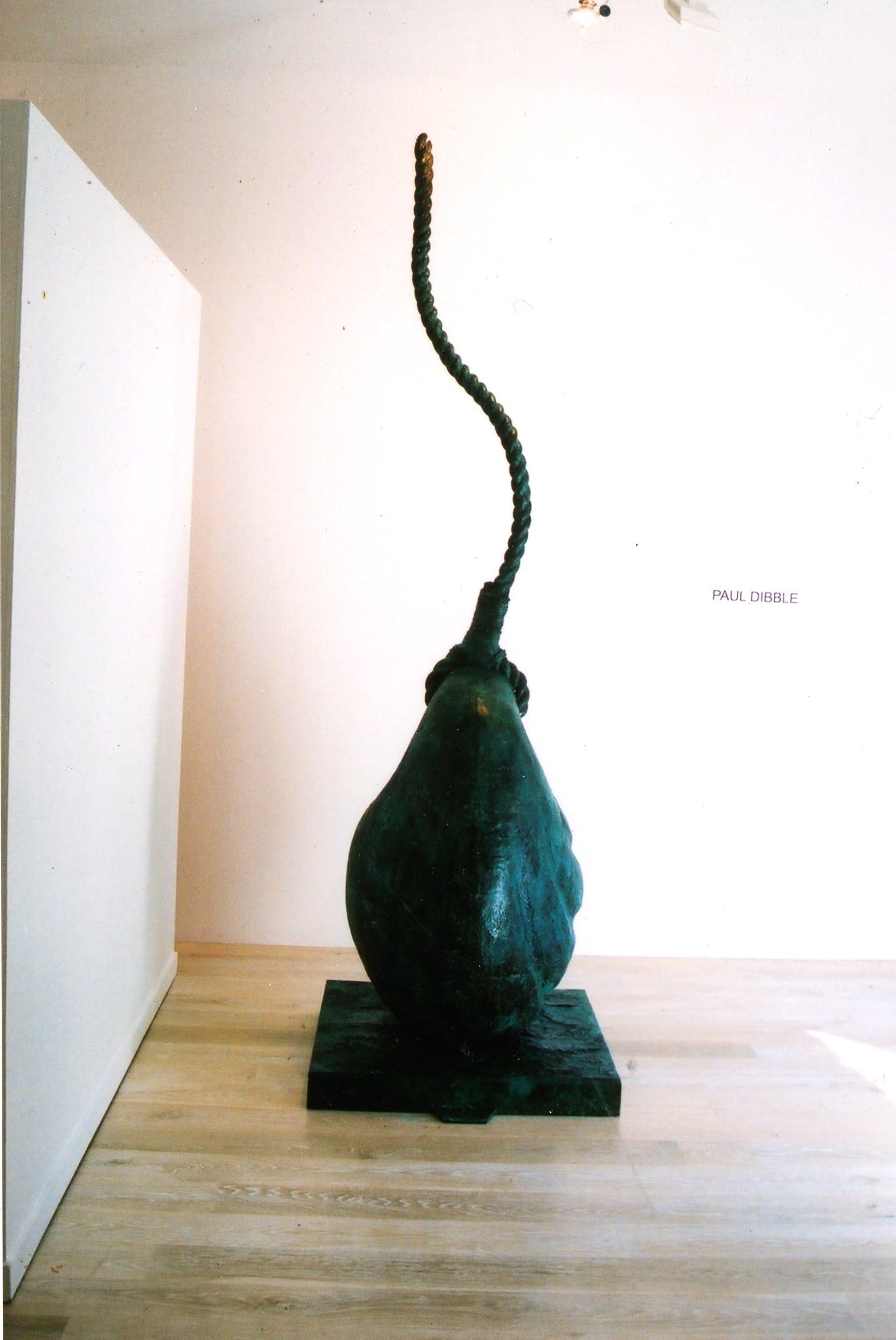

There is the Māori anchor stone, one of the archaeological relics pulled from the swampland. There are the inevitable products of fishing: eels and flounder. The voyager appears plotting the movement of early vessels. He is the stuff of many a young boy’s dreams and wonderings of tales of early charting and navigational legends (both in waka and in sailing ships), as pondered under the stars in the huge flat basin. There is the watching owl (Waitakaruru translates as the land where the owl sits on the water) seeming to be of chiselled stone of prehistoric age. There is the mermaid siren who plays a game of now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t with a fish in each hand, as though to a young child who really believes the fish has disappeared. A Cessna flies overhead memorialised in bronze, as if some cargo cult trophy; an isolated figure swims in an imaginary, endlessly flat ocean; a woman jumps, her pose frozen in a surrealist moment, caught performing a mad dance of balance.

As with many descriptions, it is the relics and small images that sum up the environment better than photos of the landscape or convoluted tales of its history. Images of flounder conjure up spear-fishing at night with the use of a light bulb fixed in a jar held below the water. On the eerily flat land, you must remember which way you came, as at night the dark swallows you up and there is no sight of home to find the way back to land. A thin boy stands with his catch, a monstrous fish we can hardly imagine he has caught.

Masterfully the elements are mixed in a potpourri of styles, changes of scale, realism to semi-abstraction, narrative to fantasy. As if flicking through a photo album, the focus shifts dizzyingly from landscape to close up, vertigo gripping. Is it an oversized feather or a giant eel next to a doll-sized boy? Or is it vice versa, and this is a feather found on our scavenges? Is the anchor portrayed in its real size or is this, too, a model of something really gigantic? Perceptions shift from realistic, even reality-mocking, to cartooned: a comic fish (a merging of a submarine and blow-up balloon) jumps to catch a fly. We accept this image as easily as our almost copy of a Māori flax pounder. Mixes of sensuous shapes stand next to formal, straight scaffolding. As the elements are lined up in their groups, we sense stories intermingled with the visual harmonies.

Each of these memories is a short story, a yarn, from this greater picture of landscape, history and destiny. It is a visual version of the childhood game of the never-ending sentence, stories strung together with a million commas. It is chapter one of an artist’s autobiography caught like a moth around a lamp from a week of dreamtime.

Paul Dibble comes from a small town called Waitakaruru. Like many New Zealand towns from the ‘50s, there is little evidence left of the community that once existed. In Dibble’s childhood it held a wharf, three to four shops, a picture theatre, a dance hall, butcher shop, bank and saleyard but these have all now disappeared. Geographically, it is located in the Hauraki Plains. Thames, the nearest town, is some 25 kilometres away. It is close to the coast on an estuary that leads out to the Gulf. The land is unusually flat and low-lying, only two feet above sea level, making the huge mud flats variable with the tide and prone to flooding. This was compensated for by the building of extensive stopbanks. Farmers settled in the old swampland and spent generations trying to turn it into economic farms. They drained the water by digging large channels, burned off the peat (there were peat fires that lasted several years and covered the area in fine ash) and broke, by blasting, the fortified logs preserved in the bog. The peat is of interest in its ability to preserve archaeological remains. These ancient artefacts were preserved better than the records of more recent settlers.