September 10 - September 10, 1995 Made in NZ

September 10 - September 10, 1995 Made in NZSolo, Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North

Text

Why have you called your exhibition “Made in New Zealand”?

Well, I think it’s New Zealand’s turn to be taken notice of. There’s a ‘90s spirit where New Zealanders feel they actually exist. Probably for the first time we do feel anchored in the South Pacific. Ever since Lange jumped up and down and said this is a nuclear free area and not part of America.

In the census forms you have to put down whether you’re Māori, Pacific Islander or European – but many people feel the term European to be antiquated – we’re all pacific islanders.

Made in NZ was once something you didn’t want to know about – it was stuff that was inflicted on you. It was cultural cringe material. NZ was never known for its good design – that all happened elsewhere. But now we appreciate Kiwiana. You never heard this word 10 years ago but now, for example, you hear about architects looking at the indigenous – exactly the sort of thing that would be pulled down before.

Made in NZ is a whole lot of things that have been sent here, half understood, and something new created from them. NZ has grabbed everything that’s come its way. As a young country it has been in a state of flux that allowed it to absorb change. Take Napier – a whole Art Deco city was built, just like that. And yet Art Deco comes from the idea of the machine, of speed, sophistication, a technological future – something that was completely European and foreign. Futurism was also about the machine – that’s why I’ve taken a nude by the Futurist artist de Chirico as the basis of one of my works (E Noho Rā De Chirico, 1994).

From the time that Europeans came here from the other side of the world there have been all sorts of distortions, misunderstandings, paradoxes and ironies. Almost overnight another culture arrived here, and established itself in considerable numbers. That’s the basis of NZ. It created a situation where people have problems coming to terms with where they are.

I’m fascinated by the absurdity of the way the English arrived here, took over, and set about establishing sheep stations in the South Pacific. I’ve always wondered what the bloody hell they thought they were doing. No refrigeration – the mind boggles!

I’ve been to Europe. We’re led to believe that European houses, for example, are so well designed, so tasteful – and its true. But I couldn’t stand it – I hated it. Even England felt to me like a foreign territory. They’re so resistant to change in Europe. I found Europeans very closed, they wouldn’t part with information when I worked in a foundry there. But the Americans I worked with didn’t give a shit. I asked one of them why. I said gosh, “You blokes hand over all this information. I’ve just come from working in Italy and they guard everything.” And he said, “In America we can give it cheap because tomorrow it will be redundant”. You know, what’s a secret today will be bloody old hat tomorrow.

Hitting America after Europe was so refreshing, such a variety and mish mash. Come back to NZ too – it was hard to believe its huge collage of crap, of tin sheds, car wrecks – it’s like a junk yard. People say its vulgar but that’s rubbish.

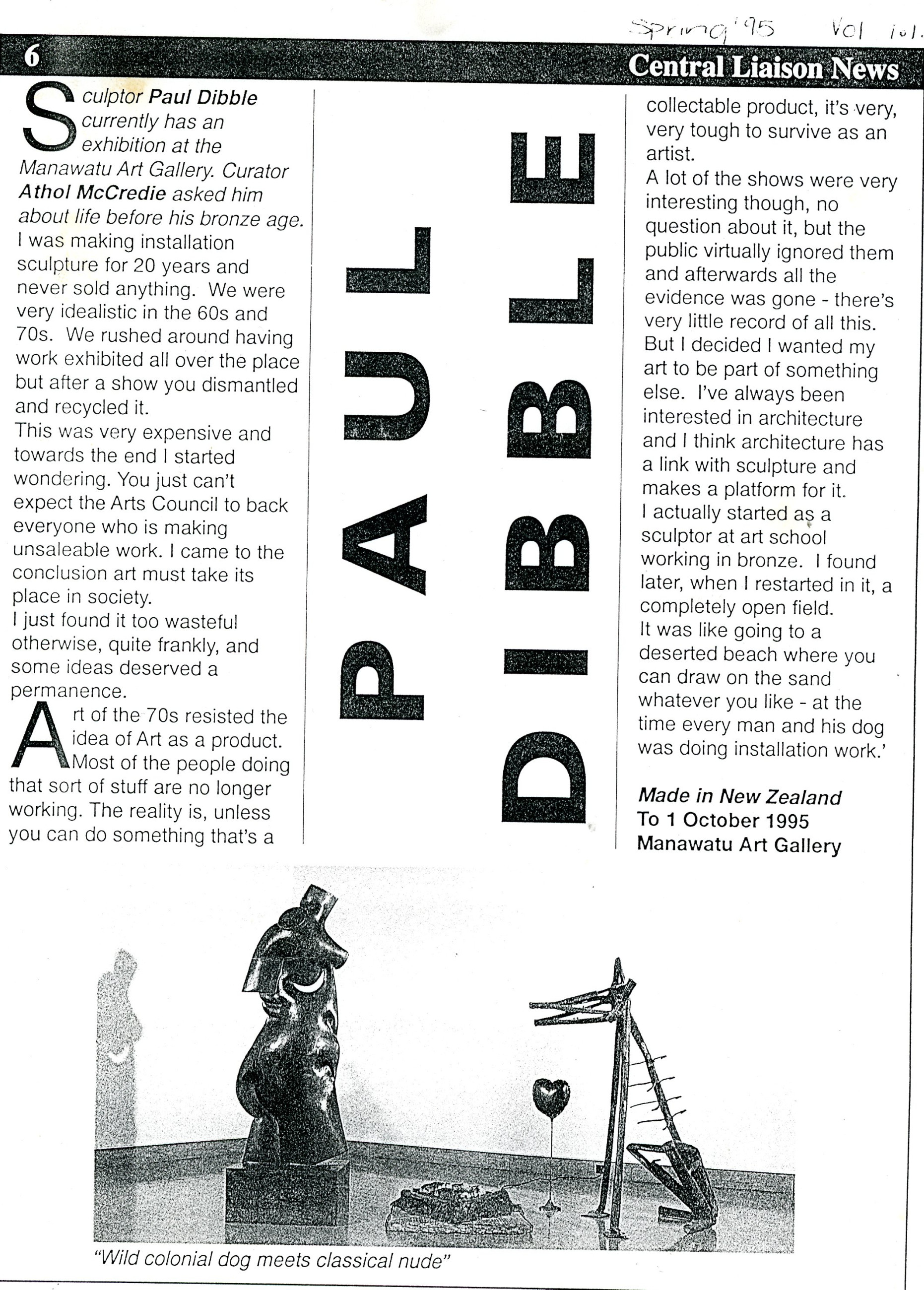

This is why in Wild Colonial Dog Meets Grand Classical Nude, 1994 I have placed a crudely made ramshackle, colonial dog, moulded in corrugated cardboard, with a cool, sophisticated European nude. The elements are basically incompatible but they’re unified by the bronze they are made from. It’s the ideas I’m interested in, not the materials of the collage that is New Zealand culture. There has been a shakedown of ideas as all this stuff has flooded in.

So that’s where I’m coming from. My work is anchored here and it comes out of living in New Zealand. I grew up in a small country town and there are two things that made an impact on me. One was the marae – it was old and spooky, certainly a presence – and not far away there was a huge war memorial statue. Every bloody town erected these things, they were completely out of place, like they’d arrived out of space, bang. As a country kid it was the first sculpture I ever saw. I hadn’t seen an art book. In this raw setting, they were awesome. You take something like this that’s essentially Italian and you put it here – it’s a displacement, a relocation, it takes on many meanings.

Lets talk more directly about meaning in your work. If someone comes up and asks what your sculptures mean, what do you say?

I actually find most people have a pretty good idea of what I’m on about. Most work you can read at different levels. I think titles are important. I like to build in a slightly subversive element, to toughen the work up, to build in a tease. One of the pieces for this show has a sheep on a pedestal, a shell, a ukelele, and a beer bottle. The beer bottle suggests that wild, uncontrolled, macho behaviour – the wild colonial boy. It’s also like a club you can hit someone with, and people do. NZ pubs are a part of our social life some people would rather not know about. I’ve found that people often dislike the bottle in this work – so you don’t need much to uncover something.

Tell me about the work you made before you were bronze casting.

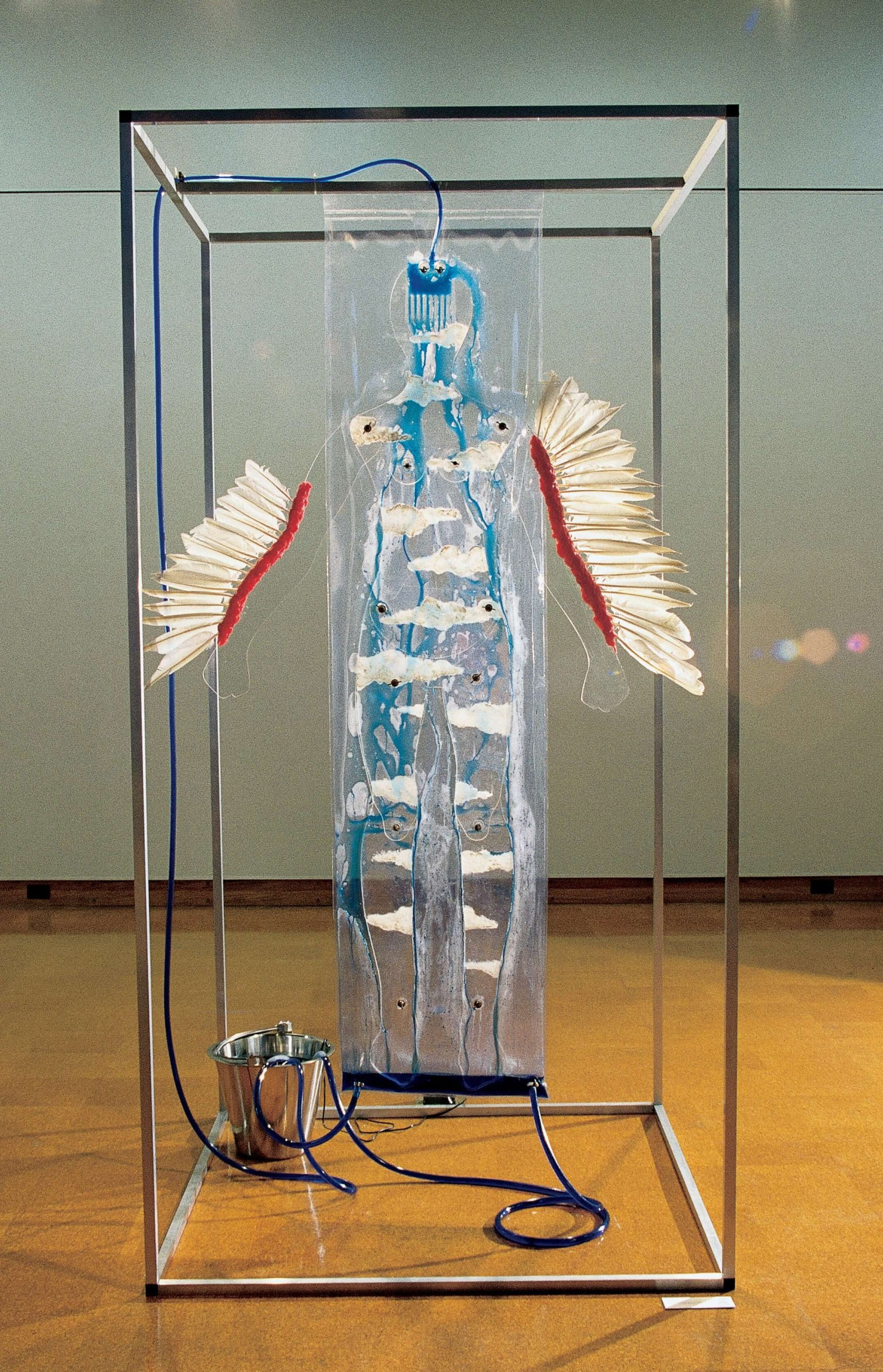

I was making installation work in the 1960s and ‘70s, as most sculptors of my generation were of course, right up to about 1980. So it’s relatively recent that I’ve got into casting things. I always maintain it was a hell of an advantage to spend all that time in installation work – it allowed me to toughen things up and to use bronze in very different ways.

Actually, I still regard the sort of work that is in this exhibition as installation work – they all have separate components. Some may be on pedestals but that is only because they are really models for much larger floor pieces.

I made installation sculpture for 20 years and never sold anything. We were very idealistic in the ‘60s and ‘70s. We rushed around having work exhibited all over the place but after a show you dismantled it and recycled it. This was very expensive and towards the end I started wondering. You can’t expect the Arts Council to back everyone who is making unsaleable work. I came to the conclusion that art must take its place in society. I just found it was too wasteful otherwise, quite frankly, and some ideas deserved a permanence.

Arts of the 1970s resisted the idea of art as product. Most of the people doing that stuff are no longer working. The reality is that, unless you can do something that’s a collectable product, it’s very, very tough to survive as an artist.

A lot of the shows were very interesting though, no question about it, but the public virtually ignored them and afterwards all the evidence was gone – there’s very little record of all this. But I decided I wanted my art to be part of something else. I’ve always been interested in architecture and I think architecture has a link with sculpture and makes a platform for it.

I actually started as a sculptor at art school working in bronze. I found later, when I restarted in it, a completely open field. It was like going to a deserted beach where you can draw on the sand whatever you like. At that time every man and his dog was doing installation work.

Your cast works nearly always have a flatness to them. Has it always been like this and did you invent the technique where you sew the shape in canvas, making a sort of bag, and then pour plaster into it to create a flattish shape for moulding?

Yes, I have been doing this from the beginning and so far as I know no-one else has done it. It actually started with pouring sand into double sided canvas to make works that were sculptures themselves.

These were hung on the wall?

Yes. I was also fibreglassing over these thin shapes, or I blew foam into them and then fibreglassed over.

I like the flatness because it promises so much from some angles but delivers so little. Like a billboard or building façade, it can be very powerful. Like the grand NZ colonial front propped up that has so little behind it. I like this. The flatness also allows me to do things like put a leaf and a nude together, makes them compatible.

I like the displacement too. I’ve always had a soft spot for classicism, for its permanence. Like the old pyramids, the way they’re stacked up. When I went to art school it was very traditional, there were classical busts all over the place and you can’t help being influenced by this. So I use the classical mathematical formula, the circles and triangles, but also subvert it, by making it all disappear into a wafer thin shape.

How do you see your work going in the future?

I sometimes think I wouldn’t mind working in steel. I do like metal sculpture though … but plate steel, I like that heavy weight of steel, and the huge sheets of it. But you need some pretty sophisticated gear to cut it and work with it.

From a written interview with Gallery curator Athol McCredie associated with the exhibition at the MAG.

A portion of the exhibition was displayed at Bowen Galleries, Wellington from October 30 - November 11, 1995.